Saturday, November 9, 2024 • 7:30 p.m.

First Free Methodist Church (3200 3rd Ave W, Seattle)

Harmonia Orchestra & Chorus

William White, conductor

Alivia Jones, soprano

Nori Heikkinen, mezzo-soprano

- tickets will also be available at the door, beginning at 6:30 p.m.

Program

George Frideric Handel (1685–1759)

Zadok the Priest, HWV 258

George Frideric Handel

Dixit Dominus, HWV 232

— intermission —

Ludwig van Beethoven (1770–1827)

Symphony No. 7 in A major, Op. 92

- full concert program (PDF)

About the Concert

This program of beloved favorites presents two aspects of Handel’s art — the majestic and the groovy — side by side, followed by Beethoven’s Seventh, a work in which he captured the majesty and the grooviness of his favorite composer (Handel) in a symphony so compelling that it draws its listeners along as if they were reading a page-turning novel.

Plan to arrive early for a 6:30 p.m. pre-concert talk by William White.

This performance will last approximately two hours, including one intermission.

Maestro’s Prelude

Dear Listener,

Picture it: Vienna. December 1826. Ludwig van Beethoven, the composer of the mighty fifth symphony and the magisterial “Ode to Joy,” lies ailing in bed, suffering from a series of (literally) gut-wrenching maladies. He’s been sickly his whole life — but this time, he won’t bounce back. Whether he knows he has only four months left to live is anybody’s guess.

On a bitterly cold winter’s morning, there is a knock at the door, which of course the great master cannot detect, his once-perfect hearing having degraded to the point of complete deafness years ago. His housekeeper answers to find a porter unloading a large wooden crate from a horse-drawn mail coach. A secretary helps lift the package inside.

A crowbar materializes and the crate’s top is pried open. Inside lies a musical treasure that the master has long dreamed of holding in his hands: forty leather-bound books containing the complete published works of George Frideric Handel. This rare item has been acquired for Beethoven by dint of the diligent efforts of a British music lover and shipped to Vienna at considerable expense.

“I received these as a gift today; they have given me great joy with this, for Handel is the greatest, the ablest composer. I can still learn from him,” Beethoven told a visitor that same afternoon. “He is the master of us all, the greatest composer that ever lived. I would uncover my head and kneel before his tomb.”

Beethoven, of course, was not known for uncovering his head and kneeling before anyone’s tomb, be that person an artist or an aristocrat. But in Handel, Beethoven found a composer who could do much with little: “Go to him to learn how to achieve great effects, by such simple means.”

“Great effects by simple means” describes exactly what you can expect from the music in tonight’s concert. The first half of the program features works from two distinct periods in Handel’s output, the early Dixit Dominus and the mature Zadok the Priest. It’s intriguing to hear how Handel’s musical language became simultaneously simpler and grander as he got older. This is the Handel that Beethoven knew and loved.

Beethoven’s music underwent a similar trajectory, and it’s hard to think of a work from his pen that better exemplifies “grandeur through simplicity” than his seventh symphony. Each of the four movements focuses on just one tiny motivic idea. And yet, listening to it, the soul is stirred to feelings of — dare I say? — majesty.

— Will White

P.S. If you would like to hear the piece of Handel’s that Beethoven (not to mention Haydn and Mozart) held in the absolute highest regard, I would recommend getting your tickets now for Messiah. Both shows may well sell out.

Solo Artists

Soprano Alivia Jones is a recent graduate of Pacific Lutheran University, where she studied voice with Holly Boaz and Soon Cho, sang with the University Chorale, and took part in several opera productions (including Le nozze di Figaro, in which she portrayed Barbarina). A native of Vashon Island, she has sung with Vashon Opera since 2008, performing in the chorus, in walk-on roles such as the Shepherd Boy in Tosca, and in the supporting role of Emmie in Albert Herring. Currently a voice student of countertenor José Luis Muñoz, she has also performed with Seattle’s acclaimed Emerald Ensemble and as a soloist with the Vashon Island Chorale.

Soprano Cassandra Willock has performed a number of operatic roles, appeared as featured soloist on the concert stage, and toured elementary schools in the Pacific Northwest as Pamina/2nd Lady in NOISE’s outreach production of The Magic Flute. Other notable roles include Angelica from Handel’s Orlando, Fiordiligi, the Countess and Rose Maurrant. She is currently a staff singer in the music program at Blessed Sacrament Church and is a student of Cyndia Sieden, with whom she studied as an undergraduate at Pacific Lutheran University before obtaining a Master’s of Music in Voice and Opera Performance from McGill University, where she studied with Dominique Labelle.

Mezzo-soprano Nori Heikkinen is a versatile performer with extensive experience as both a vocalist and instrumentalist. A member of the Cantorei ensemble at Blessed Sacrament Catholic Church, where she serves as the primary staff alto, she also sings locally with the Mägi Ensemble and the Evergreen Ensemble. A native of Madison, Wisconsin, she holds a Bachelor of Arts in Computer Science and Linguistics from Swarthmore College. During her time in the Bay Area, she sang with the San Francisco Symphony Chorus and the International Orange Chorale of San Francisco. Currently a voice student of José Luis Muñoz, she has previously studied viola with Joseph de Pasquale, Judy Geist and Elena Denisova.

- Learn more: noriheikkinen.com

Tenor Charles Lyon Stewart hails from Washington, DC, where he began singing with the National Cathedral Choir at age nine and made his solo debut with the National Symphony in the annunciation scene of Handel’s Messiah at 13. He holds a Bachelor of Music in vocal performance from Indiana University and is now a cardiothoracic intensive care nurse enrolled in the Doctor of Nursing Practice program at the University of Washington. Recent solo performances include Britten’s Serenade

for Tenor, Horn and Strings with the Emerald City Chamber Orchestra.

Born in Minneapolis, baritone Gabriel Salmon grew up in Palo Alto before attending St. Olaf College, from which he earned a Bachelor of Arts in music and another in economics. After stints in Denver and Richmond, Virginia, he moved to Seattle a year and a half ago and immediately joined Harmonia. He also currently sings with Epiphany Parish Church and previously with the St. Olaf Choir, Minnesota Opera and Picnic Operetta.

Program Notes

George Frideric Handel

Zadok the Priest, HWV 258

Handel was born in Halle, Germany, on February 23, 1685, and died in London on April 14, 1759. He composed this anthem in September 1727 for the coronation of King George II on October 11 of that year. In addition to chorus, the work employs 2 oboes, 2 bassoons, 3 trumpets, timpani, organ and strings.

Georg Friedrich Händel, the son of a respected barber-surgeon and a clergyman’s daughter, demonstrated an affinity for music from an early age, studying keyboard and composition with Friedrich Zachow in his hometown of Halle, about 35 km northwest of Leipzig in Saxony. The elder Händel died when Georg Friedrich was 11 and while the boy did matriculate at the University of Halle in 1702 (in accordance with his father’s wishes that he study law), there is some question as to whether he actually attended any classes. Even though he was Lutheran, he served for a year as organist at the Calvinist Cathedral in Halle before moving to Hamburg, where he played second violin and harpsichord in the city’s opera orchestra.

In Hamburg, Handel forged what would become lifelong friendships with composers Georg Philipp Telemann and Johann Mattheson (in spite of a 1704 disagreement that led to Mattheson nearly killing Handel in a duel) and by 1705 had composed his first opera, Almira, Königin von Castilien, written (as was the fashion at the time) in the Italian style; three more (now mostly lost) quickly followed.

In the latter half of 1706 Handel headed to Italy (at the invitation of Prince Ferdinando de Medici, according to legend — if not fact), stopping in Florence and by the end of the year arriving in Rome. Unfortunately for Handel, who presumably sought to learn the art of Italian opera, an ongoing papal ban on staged performances forced him to instead compose liturgical music (including his Dixit Dominus) and at least 60 chamber cantatas during his visits to the Eternal City. He did, however, produce two operas during his years in Italy: Rodrigo debuted in Florence in October 1707, and Agrippina was a smash hit in Venice January 1710, the Venetians hailing il caro Sassone (“the beloved Saxon”).

Upon his return to Germany, Handel made a stop at the court of Georg Ludwig, Elector of Hanover, whose mother, Sophia, wrote about “the music of a Saxon who surpasses everyone who has ever been heard in harpsichord-playing and composition.” The elector was similarly impressed and within 10 days had hired Handel as his Kapellmeister.

Sophia, it so happened, was a granddaughter of James I of England and 56th in line to the British throne, currently occupied by her first cousin, Queen Anne. But the 55 men and women ahead of Sophia were Catholic, so the British Act of Settlement of 1701 (which ensured a Protestant monarch) made her Anne’s heir. Thus when Handel, upon gaining employment from Georg Ludwig, immediately requested a year’s leave of absence to visit London, the Elector of Hanover may have been motivated to acquiesce through a desire to curry favor there, or perhaps to have an employee who could report back on the goings-on at the court of Queen Anne.

In London, where Italian opera was just coming into vogue, Handel made a splash with several works that premiered at the Queen’s Theatre on Haymarket Street. Between occasional trips back to Germany, he also composed an Ode for the Birthday of Queen Anne and other works with political overtones (such as the Utrecht Te Deum and Utrecht Jubilate). Upon Anne’s death on August 1, 1714, just weeks after the passing of her cousin Sophia, Georg Ludwig ascended to the British throne as King George I. The new monarch inherited the court composers of his predecessor, so Handel had no official position in spite of George I previously being his de facto employer, but he remained in London with the king’s blessing and occasionally composed at his request, most notably the Water Music of 1717.

Over the next decade, Handel continued to produce highly successful operas for Haymarket. On February 20, 1727, the House of Lords passed legislation naturalizing the German composer and George I granted his assent, making Handel a British citizen. When George I died less than four months later, his son ascended to the throne as George II, postponing a formal coronation until October. Ordinarily, any new music for such a ceremony would have been the responsibility of the Organist and Composer of the Chapel Royal, but after that gentleman died on August 14, London newspapers reported in early September that “Mr Hendel, the famous Composer to the opera, is appointed by the King to compose the Anthem at the Coronation which is to be sung in Westminster Abbey at the Grand Ceremony.”

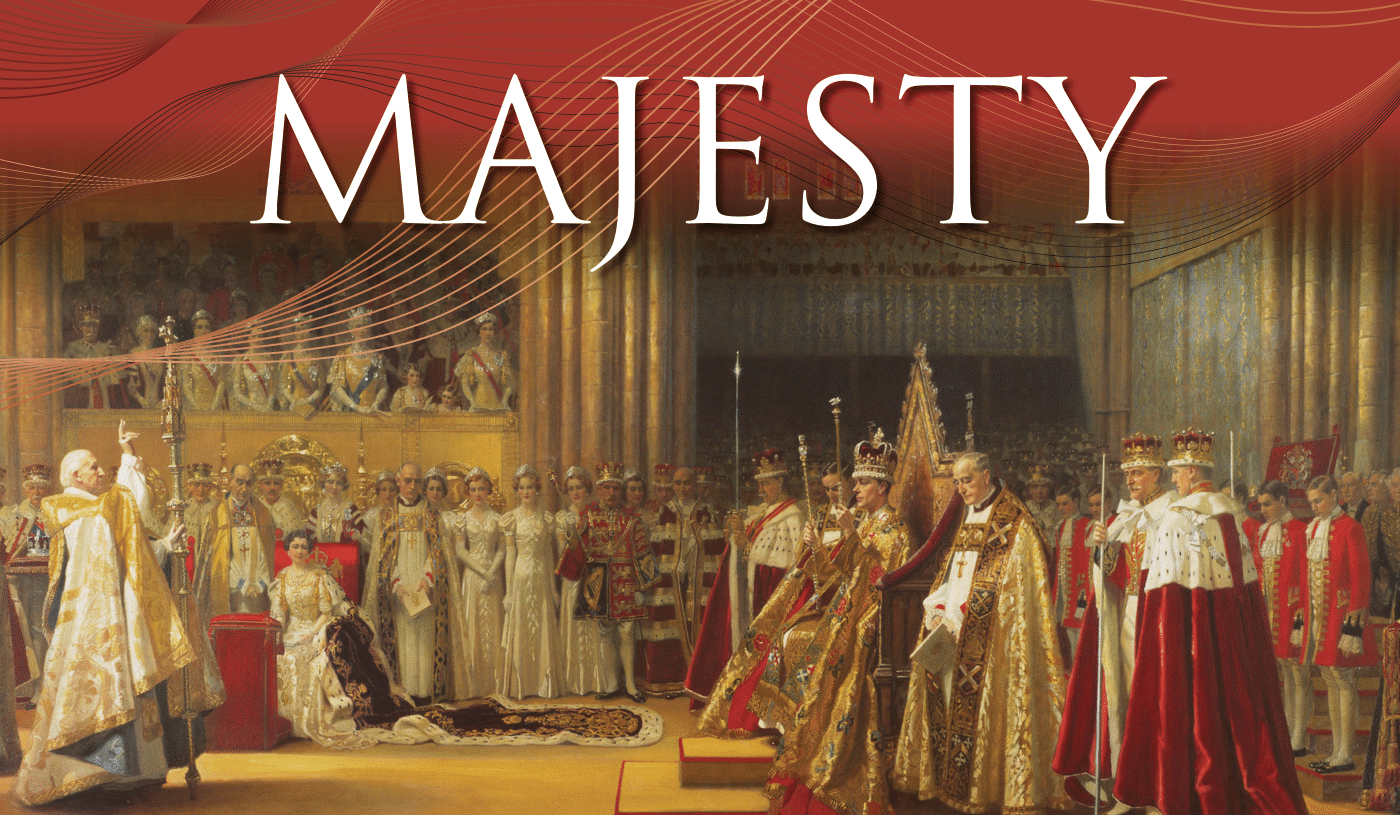

Handel actually composed four anthems for the occasion: Zadok the Priest, The King Shall Rejoice, Let Thy Hand Be Strengthened and My Heart is Inditing. For the first of these, he drew upon I Kings 1:38–40. A hushed orchestral introduction sets the stage for one of Handel’s most glorious choral entrances, followed by lively dance-like music in 3/4 time before returning to 4/4 for a suitably regal conclusion. In the ultimate tribute to England’s greatest adopted composer, each subsequent coronation ceremony for a British monarch (including that of King Charles III in 2023) has included Zadok the Priest.

George Frideric Handel

Dixit Dominus, HWV 23

Handel composed this motet in Rome, completing it in April 1707. It employs SSATB chorus (with SSATB solos), strings and basso continuo.

The precise circumstances for which Handel wrote his Dixit Dominus remain a mystery, but we do know that he completed it in Rome by early April of 1707 and that it is his earliest surviving autograph score of a large-scale work. A few months later he would produce several other liturgical pieces (including a Nisi Dominus, whose opening violin arpeggios resemble those that begin Zadok the Priest) likely premiered at a vespers service in July of that year at the Carmelite church of Santa Maria di Monte Santo, so some have theorized (with little or no evidence) that Dixit Dominus was conceived as part of a large-scale vespers service, akin to Claudio Monteverdi’s Vespro della Beata Vergine of 1610 or Mozart’s later Vesperae solennes de confessore.

“A more recent theory,” Handel biographer Jonathan Keates writes, suggests it “was written as a psalmus in tempore belli,” or psalm in time of war, a hypothesis supported by the bellicose nature of the psalm’s poetry, such as “fill the places with destruction, and shatter the skulls in the land of the many.” Whatever its genesis, it stands, according to Richard Freed, as “one of the grandest, as well as earliest, confirmations of Handel’s mastery of the Italian style and of its integration into his own personal language.”

Handel absorbed some of that Italian style directly from the masterful composer and violinist Arcangelo Corelli. “The Corellian lyricism and suppleness of the string writing,” in the Dixit Dominus, writes Keates, “determine the character of the entire work, essentially a series of vocal concerto movements, relentless in its momentum and dazzling in its grandness of design.” Indeed, the opening movement of Dixit Dominus exhibits trademarks of the Corelli-style concerto grosso, with solo passages for voices and violins alternating with tutti sections for the entire ensemble. Midway through, Handel introduces a cantus firmus (long, drawn-out notes beginning with words “donec ponam”) seemingly based on plainchant tones, which soar over a repeated rhythmic figure that calls to mind his setting of the word “Hallelujah” from that most famous chorus in Messiah, composed three decades later.

Next comes an aria for alto and continuo, then a soprano aria accompanied by full orchestra, both of which, contends Freed, “show the clear influence of the solo cantatas of Alessandro Scarlatti.” The chorus opens the fourth movement with a grand oration that leads to a quick 3/4 tempo, which eventually draws to a close with a striking diminuendo to pianissimo. Next up is a double fugue (“Tu es sacerdos”) that Handel would later reuse (as “He led them through the deep”) in his oratorio Israel in Egypt.

“Dominus a dextris tuis” features a relentless bass line under duets and a bass solo before the entire ensemble enters, with violins and violas joining the propulsive eighth-note pattern of the continuo. This yields to “Judicabit in nationibus,” which becomes increasingly more active and bellicose, culminating with a highly percussive setting of the word “conquassabit” for the shattering of skulls. “De torrente” allows a moment of repose, with strings emulating the ebb and flow of a brook as two sopranos float above the tenor and bass voices of the chorus.

Following tradition, Handel appends the “Gloria patri” (the doxology) to Psalm 110, laying down a groove in the continuo as the basis for a free fugue and adding the plainchant from the opening movement for the text “Sicut erat in principio” (“As it was in the beginning”). The tempo kicks into high gear at “et in saecula saeculorum,” with a new fugue subject starting on a repeated note (that becomes shorter and shorter) to close what Freed calls “as stunning a piece as Handel produced in his Italian years, pointing surely and confidently to the glories to come in England.”

Ludwig van Beethoven

Symphony No. 7 in A major, Op. 92

Beethoven was born in Bonn on December 16, 1770, and died in Vienna on March 26, 1827. He began this work during 1811, completing it on April 13, 1812, and conducting the first performance on December 8, 1813. The score calls for pairs of woodwinds, horns and trumpets, plus timpani and strings.

The December 1813 concert at which Beethoven’s seventh symphony premiered was among the most successful of the the composer’s career, but while the symphony was greeted with acclaim, it was overshadowed by the debut of another Beethoven work, Wellington’s Victory, which history has treated less than kindly. The occasion — a benefit for Bavarian soldiers wounded at the Battle of Hanau, which had taken place five weeks earlier as Napoleon retreated to France — was organized by Johann Nepomuk Maelzel (known as developer of the metronome). The previous summer, Maelzel had commissioned Beethoven to write Wellington’s Victory (a “battle symphony” about a Napoleonic defeat by British forces in Spain) for his panharmonicon, a sort of “mechanical chamber orchestra,” although the piece received its premiere here in a version for orchestra.

The circumstances of the first hearing of Beethoven’s Symphony No. 7 led some to conclude that it was a “war symphony,” but in fact he had completed it more than a year and a half earlier — this high-profile concert merely provided an auspicious opportunity for its debut. If anything, Beethoven’s Seventh is a symphony about rhythm: Richard Wagner famously called it “the apotheosis of the dance, the dance in its highest condition, the happiest realization of the movements of the body in ideal form.”

The symphony opens with a lengthy 4/4 introduction, in which Beethoven maneuvers from the home base of A major through other keys in ways that must have shocked the work’s first listeners. He cleverly transitions to the 6/8 Vivace by breaking apart repeated sixteenth-note E’s in the flute, oboe and violins and then reassembling them into a long- short-medium rhythm (— - –) that will single-mindedly dominate the remainder of the movement, which Beethoven biographer Jan Swafford calls “a titanic gigue.”

The 2/4 Allegretto in A minor is a solemn (but not slow) processional, also based on an endlessly repeated rhythm (— - - — —), with major-key interludes. The opening material undergoes numerous variations, including a fugal treatment. The audience at the premiere demanded an encore. “Here commences, as much as in any single piece,” asserts Swafford, “the history of Romantic orchestral music.”

The F-major scherzo, full of unexpected outbursts and misdirections, features a somewhat slower D-major trio (purportedly based on an Austrian pilgrims’ hymn).

“The intention of the Allegro con brio finale,” contends Swafford, “is to ratchet the energy higher than it yet has been. Few pieces attain the brio of this one.” Writing in what he called his aufgeknopft (“unbuttoned”) style, Beethoven pushes the orchestra to extremes, including the first use of a triple-forte dynamic in any of his symphonies.

— Jeff Eldridge