Dvořák in America

Saturday, November 11, 2017 • 7:30 p.m.

First Free Methodist Church (3200 3rd Ave W)

Orchestra Seattle

Seattle Chamber Singers

William White, conductor

Catherine Haight, soprano

José Rubio, baritone

Program

Leo Sowerby (1895 –1968)

Comes Autumn Time

Franz Joseph Haydn (1732 –1809)

Hunting Chorus from The Seasons, Hob. XXI:3

Antonín Dvořák (1841 –1904)

Te Deum, Op. 103

Robert Lowry (1826 –1899) (arr. Copland/orch. White)

“At the River” from Old American Songs, Set 2

— intermission —

Antonín Dvořák

Symphony No. 9 in E minor, Op. 95 (“From the New World”)

About the Concert

In 1892, the Czech composer Antonín Dvořák arrived in New York to lead the National Conservatory of Music in America, bearing with him the score for his majestic Te Deum for chorus, soloists and orchestra, which he conducted at a concert celebrating Columbus Day. During his stay in the United States, Dvořák composed his “New World” Symphony, which has rightfully gone on to become one of his most acclaimed works. In America, we think of autumn as a time for celebration — reflected in the delightful overture Comes Autumn Time by Chicago composer and organist Leo Sowerby, as well as the “Hunting Chorus” from Haydn’s The Seasons.

About the Conductor

William C. White is a conductor, composer, teacher, writer and performer based in Portland, Oregon. For four seasons (2011–2015) he served as assistant conductor of the Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra, working closely with music director Louis Langrée and an array of guest artists, including John Adams, Philip Glass, Jennifer Higdon, Itzhak Perlman and James Conlon. As part of his appointment with the CSO, he also served as conductor of the Cincinnati Symphony Youth Orchestra, a tenure notable for its tours to Chicago and New York, both featuring all 20th- and 21st-century repertoire, as well as community-wide choral collaborations raising funds for charity. During the 2015 –2016 season, Mr. White served as interim music sirector of Portland’s Metropolitan Youth Symphony, leading their season-end tour to Beijing.

Mr. White has long-standing associations with a number of musical organizations, including the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, where he has regularly given pre-concert lectures since 2008. For three seasons, he was music director of Cincinnati’s Seven Hills Sinfonietta, a period that saw remarkable growth for the organization as a whole.

As composer, Mr. White has written music for the concert stage, theater, cinema and church, and his music has been performed throughout North America as well as in Asia and Europe. His major works include a symphony in three movements and several narrated works for young audiences. His music has been recorded on the MSR Classics and Cedille Records labels.

Mr. White earned a masters degree in conducting from Indiana University’s Jacobs School of Music, studying with David Effron and Arthur Fagan. He received a B.A. in music from the University of Chicago, where his principal teacher was the composer Easley Blackwood. In 2004, he began attending the Pierre Monteux School for Conductors under the tutelage of Michael Jinbo, later serving as the school’s conducting associate and then as its composer-in-residence.

Hailing from Bethesda, Maryland, Mr. White began his musical training as a violist. He maintains a significant career as a clinician, arranger and guest conductor, particularly of his own works. His orchestral arrangements, including “Happy,” “Dear Theodosia” and an orchestral suite from Sweeney Todd, have been performed by orchestras throughout the United States.

In 2015, Mr. White launched a YouTube series called Ask a Maestro, where he answers questions about the world of classical music. Recordings of his works can be heard at his Web site, where he also maintains a blog and publishing business.

About the Soloists

Soprano Catherine Haight appears frequently with the region’s most prestigious musical organizations, regularly performing in Pacific Northwest Ballet’s Carmina Burana and The Nutcracker. Reviewing PNB’s world premiere of Christopher Stowell’s Zaïs, The Seattle Times called her singing “flawless.” She appears as soprano soloist on the OSSCS recording of Handel’s Messiah, the Seattle Choral Company recording of Carmina Burana, and on many movie and video game soundtracks, including Pirates of the Caribbean, Ghost Rider and World of Warcraft. Recent concert performances include Handel’s Israel in Egypt and Bach’s Mass in B Minor and St. John Passion with OSSCS, Barber’s Knoxville: Summer of 1915 with https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ln5zy4cqbZI Seattle Collaborative Orchestra and Richard Strauss’ Four Last Songs at Seattle Pacific University, where she has served on the voice faculty since 1992. Learn more: spu.edu

Baritone José Rubio is equally comfortable in the concert hall and on the operatic stage. His Carnegie Hall recital debut met with great acclaim, The Opera Insider proclaiming it “nothing short of stellar” and describing the performance as “an hour of intensely passionate singing and playing. It could have gone on forever without complaint.” Mr. Rubio’s recent engagements include Tonio in I Pagliacci with Vashon Opera, Falke in Die Fledermaus with Tacoma Opera, bass solos in Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony with Philharmonia Northwest at Benaroya Hall, and the role of notorious gangster Legs Diamond in Evan Mack’s opera Roscoe with the Albany Symphony (featuring Deborah Voigt as the female lead). He is featured on recordings of two Philip Glass operas on the Orange Mountain Music label, Orpheé and Galileo Galilei, and can also be heard on Albany Records’ world premiere recording of Evan Mack’s Angel of the Amazon. Learn more: joserubiobaritone.com

Program Notes

Leo Sowerby

Comes Autumn Time

Sowerby was born May 1, 1895, in Grand Rapids, Michigan, and died July 7, 1968, in Port Clinton, Ohio. The original version of Comes Autumn Time, for solo organ, received its first performance, by Eric DeLamarter, in October 1916; on January 18, 1917, DeLamarter conducted members of the Chicago Symphony in the premiere of an orchestral version, scored for pairs of woodwinds (plus piccolo and bass clarinet), 4 horns, 3 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, glockenspiel, chimes, harp, celesta and strings.

Leo Sowerby began composing at age 10, and at 14 moved from his hometown of Grand Rapids to Chicago, where he studied composition with Arthur Olaf Anderson at the American Conservatory of Music. After service as a clarinetist and bandmaster during World War I, he became the first composer to receive the Rome Prize from the American Academy in Rome. Returning to Chicago, he joined the faculty of the American Conservatory and served as organist and choirmaster at St. James’ Episcopal Church until 1962, when he moved to Washington, D.C., to become the founding director of the College of Church Musicians at the National Cathedral.

A prolific composer, Sowerby produced five symphonies, a dozen concertos, and numerous songs, choral works and pieces for solo organ. In 1946 he received the Pulitzer Prize in Music for his cantata Canticle of the Sun. William Ferris, a student of Sowerby’s, called him “the most complete musician I ever knew, an amazing amalgam of what was American at the time.”

In October 1916, Sowerby received a request from Eric DeLamarter, the organist at Chicago’s Fourth Presbyterian Church, for a solo work to feature on a recital. Working quickly, Sowerby took inspiration from Canadian poet Bliss Carman’s “Autumn,” first published in the October 1916 edition of The Atlantic and reprinted in the October 5 edition of the Chicago Tribune:

Now when the time of fruit and grain is come,

When apples hang above the orchard wall,

And from the tangle by the roadside stream

A scent of wild grapes fills the racy air,

Comes Autumn with her sun-burnt caravan,

Like a long gypsy train with trappings gay

And tattered colors of the Orient,

Moving slow-footed through the dreamy hills.

The woods of Wilton at her coming wear

Tints of Bokhara and of Samarcand;

The maples glow with their Pompeian red,

The hickories with burnt Etruscan gold;

And while the crickets fife along her march,

Behind her banners burns the crimson sun.

Sowerby cautioned that the overture was “a response to the suggestion of moods, rather than a literal translation of the verses into tone,” calling it “an expression of the full joy of Autumn. The piece is not long, and is in regular sonata form, except that in the recapitulation, the second theme precedes the entrance of the first. The key is A major; 2/4 time.”

The following January, DeLamarter conducted members of the Chicago Symphony in a concert devoted exclusively to Sowerby’s music, for which occasion the composer orchestrated Comes Autumn Time. CSO music director Frederick Stock attended the performance and subsequently commissioned a number of orchestral works from Sowerby. Comes Autumn Time became one of Sowerby’s first compositions to receive widespread performances, including several by the New York Philharmonic, whose program annotator described the overture as “based on two contrasting themes, one an exuberant melody for full orchestra, the other a haunting tune of pastoral character for clarinet and other wind instruments.” A New York Times review declared the work “brief, brilliant and effective.”

Franz Joseph Haydn

“Hört das laute Getön” from Die Jahreszeiten, Hob. XXI:3

Haydn was born in Rohrau, Lower Austria, on March 31, 1732, and died in Vienna on May 31, 1809. He began work on his oratorio The Seasons in 1799, completing it in 1801 and conducting the first performance on April 24 of that year.

History does not remember Dutch-born Gottfried van Swieten for his work as an Austrian diplomat nor for his amateur compositions but rather for his profound influence on two of music’s great geniuses: Mozart and Haydn. Baron van Swieten introduced many important works of Handel and Bach to Mozart and Haydn, and pestered Haydn to write a grand oratorio in the style of Handel. When Haydn finally gave in, he produced one of his greatest masterpieces, The Creation, with van Swieten editing the English libretto and translating it into German.

After the success of The Creation, van Swieten pressured Haydn to tackle another oratorio, this one loosely based on The Seasons, an epic blank-verse poem by Englishman James Thomson. In four parts (one for each season), Die Jahreszeiten mixes choruses and ensemble numbers with recitatives and arias for bass, tenor and soprano (in the roles of characters named Simon, Lucas and Hanne). Near the end of the “Autumn” section comes a hunting chorus that, as Michael Steinberg notes, displays Haydn’s “wonderful art of continuously unfolding and surprising variation. Beginning in D but ending in E♭, it also revels in the reckless abandoning of the Classical harmonic tradition. All those hunting calls, blared lustily by four horns in unison, are real ones!”

Antonín Dvořák

Te Deum, Op. 103

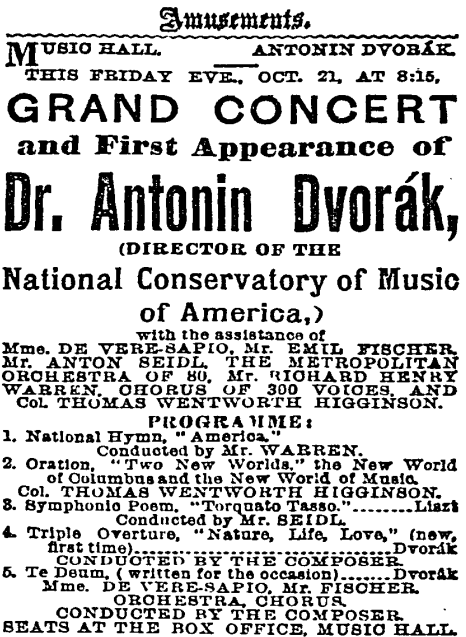

Dvořák was born September 8, 1841, in the Bohemian town of Nelahozeves (near Prague, now in the Czech Republic), and died on May 1, 1904, in Prague. He composed this work between June 25 and July 28, 1892, conducting the premiere at Carnegie Hall on October 21 of that year. In addition to vocal soloists and SATB chorus, the work calls for pairs of woodwinds (with one oboe doubling English horn), 4 horns, 2 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, triangle, cymbals, bass drum and strings.

The two major works on this evening’s program may never have come to be were it not for New York philanthropist Jeannette Meyer Thurber (1850–1946). In 1885 she founded the National Conservatory of Music in America, modeled after the Paris Conservatoire (where she had studied as a teen). Jacques Bouhy, a renowned Belgian baritone who had created the role of Escamillo in Carmen, served as the school’s first director. The Conservatory had a remarkably progressive admissions policy, encouraging women, minorities and the physically disabled to enroll, and arranged for students to attend regardless of their ability to pay tuition. Deciding to hire a top-rank composer to succeed Bouhy, Thurber set her sights on Antonín Dvořák.

Trained as an organist, Dvořák played viola in Prague’s Bohemian Provisional Theater Orchestra during the 1860s, supplementing his income by giving piano lessons. Although his Op. 1 dates from 1861, his music apparently received no public performances until a decade later, when he quit the orchestra to devote more time to composing. While his compositions began to achieve some measure of success in Prague, he remained in need of two things: money and wider recognition of his talents.

In 1874, Dvořák applied for the Austrian State Stipendium, a composition prize awarded by a jury consisting of composer Johannes Brahms, music critic Eduard Hanslick and Johann Herbeck, director of the Imperial Opera. Brahms in particular was overwhelmingly impressed by the 15 works Dvořáksubmitted, which included a song cycle, various overtures and two symphonies. Dvořák received the 1874 stipend, and further awards in 1876 and 1877, when Hanslick wrote to him that “it would be advantageous for your things to become known beyond your narrow Czech fatherland, which in any case does not do much for you.”

Seeking to help in this regard, Brahms passed along a selection of Dvořák’s music to his own publisher, Fritz Simrock, who issued Dvořák’s Op. 20 Moravian Duets, then commissioned some four-hand–piano pieces modeled after Brahms’ successful Hungarian Dances. These Op. 46 Slavonic Dances proved so popular that they launched Dvořák’s worldwide fame.

In the spring of 1891, shortly after Dvořák became a professor of composition at the Prague Conservatory, Thurber offered the composer a job as director of her school in New York — at 25 times his current salary. Negotiations ensued over the next few months until Dvořák, initially reluctant, accepted. His contract required him to give six concerts annually, and one of these was planned for shortly after his arrival, to be held on October 12, 1892, at the Metropolitan Opera House in celebration of the 400th anniversary of Columbus landing in the Western Hemisphere.

Thurber asked Dvořák to compose a choral work for the event, setting an 1819 poem by Rodman Drake that extolled the virtues of the U.S. flag. The text did not arrive in a timely manner, however, so the composer went with Thurber’s suggested backup plan “that Dr. Dvořák choose some Latin Hymn such as Te Deum laudamus or Jubilate Deo or any other which would be suitable for the occasion.” Dvořák opted for a Te Deum. Meanwhile, a fire at the Metropolitan Opera forced the cancellation of their 1892–1893 season and necessitated moving the Dvořák welcoming concert to October 21 at the newly opened Carnegie Hall:

A devout Catholic, Dvořák had previously composed two lengthy settings of religious texts — a Stabat Mater (written in 1876 and 1877 as a reaction to the death, in quick succession, of three of his children) and a Requiem (on a commission from a music festival in Birmingham, England, where he conducted the premiere in 1891) — along with a brilliant setting of Psalm 149 and a Mass in D major (composed in 1887 but orchestrated in 1892 immediately before he began writing the Te Deum).

The Te Deum is a Christian hymn of praise probably dating from the fourth century. Lully, Handel, Haydn, Mozart, Berlioz, Verdi and Bruckner all created settings of the Te Deum, typically for ceremonial occasions of public rejoicing. Dvořák broke the text into four sections, creating a miniature symphony that shares an opening key (G major) and a general pastoral mood with his Symphony No. 8, composed three years prior.

Pounding timpani open the work, with the chorus exulting in praise of the Lord. The music softens for the central “Sanctus” section, led by solo soprano. A brief reprise of the boisterous opening material leads without pause to the slow movement, which alternates dramatic brass fanfares with the baritone soloist singing “Tu Rex gloriae, Christe.” The mood eventually relaxes, with the chorus (first the women, then the men) answering the soloist (“Te ergo quaesumus”).

The third movement takes the form of a symphonic scherzo, leading directly to the finale, initially dominated by the solo soprano. The baritone soloist joins her for the “Benedicamus” and material from the first movement returns for a brilliant “Alleluja!”

Antonín Dvořák

Symphony No. 9 in E minor, Op. 95

Dvořák composed this symphony between January 10 and May 24, 1893. Anton Seidl conducted the New York Philharmonic in the first performance on December 15 of that year. The score calls for pairs of woodwinds (with one flute doubling piccolo and one oboe doubling English horn), 4 horns, 2 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, triangle, cymbals and strings.

The first work Dvořák completed in America was the cantata The American Flag, a setting of the Drake poem he had promised Thurber. He then began a symphony that would occupy him during the first five months of 1893. On the day he completed it, he received news that his four youngest children were on their way to join the rest of the Dvořák family in America. They spent the summer in Spillville, Iowa, home to an enclave of Czech immigrants. Returning to New York City, Dvořák stopped at Niagara Falls: “That will be a symphony in B minor!” Alas, his ninth symphony would be his last.

Back in New York, Dvořák offered the premiere of his E-minor symphony to Hungarian conductor Anton Seidl and the New York Philharmonic, hastily adding a subtitle, “From the New World.” The premiere was an unparalleled success. “Any one who heard it could not deny that it was the greatest symphonic work composed on American soil,” Henry Finck wrote in the New York Evening Post. “A masterwork has been added to the symphonic literature.”

Finck’s assessment of the work was no overstatement: it quickly became Dvořák’s most famous composition. But confusion has ensued ever since about just how much of it came from the “New World.” In interviews, Dvořák discussed his study of indigenous American music, but cautioned: “It is merely the spirit of Negro and Indian melodies which I have tried to reproduce in my new symphony. I have not actually used any of the melodies.”

Harry Burleigh, an African-American student at the Conservatory who befriended Dvořák, helped familiarize him with spirituals and plantation songs, but the Czech composer’s only exposure to Native-American music had come from attending Buffalo Bill’s Wild West show with Thurber. American literature definitely influenced the conception of the “New World,” but just how much different it would have been had Dvořák composed it in Prague remains an open question. This concert presents a rare opportunity to compare music Dvořák wrote immediately before leaving for the United States (the Te Deum) with his first major work composed on this continent.

The symphony begins with a slow introduction before horns launch into a vigorous E-minor melody, followed by a succession of other catchy tunes that undergo an extensive and inventive development.

Dvořák told the New York Herald that the second movement “is in reality a study or a sketch for a longer work, either a cantata or an opera which I propose writing, and which will be based on [Henry Wadsworth] Longfellow’s Hiawatha,” an epic poem that Dvořák knew from a Czech translation; Thurber had given him a copy in English, hoping he would write a “Great American Opera.” “The opening chords act as the frame that separates the legend from the rest of the world,” writes Michael Beckerman in New Worlds of Dvořák. “The modulation that mysteriously steers us to the key of D♭ major also serves as a musical ‘Once upon a time.’ ” Dvořák told the New York Daily Tribune’s Henry Krehbiel that “Hiawatha’s Wooing” (Chapter 10 of the Longfellow poem) inspired the movement; the famous English horn theme may have represented the homeward journey of Hiawatha and his bride Minehaha. The composer originally assigned the melody to solo clarinet, but eventually opted for English horn because it more closely resembled the timbre of Burleigh’s voice. He had also conceived the theme in a significantly faster tempo and in C major (but transposed it up half a step in order to use the “once upon a time” chords as a bridge between the first and second movements).

The funeral march of the slow movement’s central section, according to Burleigh, represented “the famine scene” in Hiawatha. “It had a great effect on [Dvořák] and he wanted to interpret it musically.” In his analysis of the work, Krehbiel noted “a striking passage in the middle of the movement, constructed out of a little staccato melody, announced by the oboe and taken up by one instrument after another until it masters the orchestra, as if it intended to suggest the gradual awakening of animal life on the prairie scene.” Dvořák would not hear the bluebird and the robin Longfellow mentions in Hiawatha until his travels to Iowa after writing the symphony, but he did utilize material from a book on birdsong given to him in New York.

“The Scherzo of the symphony was suggested by the scene at the feast in Hiawatha where the Indians dance,” Dvořák told the Herald. The structure of the opening section closely follows the action in Longfellow’s poem, but the musical form recalls Beethoven. The central trio (which Breckerman suggests may have been inspired by the Hiawatha chapter “The Son of the Evening Star”) features music that would be at home in the Slavonic Dances, along with trilling woodwinds evoking more birdsong (this time Dvořák’s beloved pigeons).

In the finale, the brass introduce another bold E-minor theme, the first of several new tunes that mix with recollections of melodies from the preceding three movements (including the “once upon a time” chords from the Largo) in thrilling fashion. Although Dvořák left no account of programmatic inspirations for the finale — and while much of the thematic material is thoroughly Czech in nature — Beckerman hypothesizes the composer may have structured the movement after the climactic battle in “The Hunting of Pau- Puk-Keewis,” in which Hiawatha confronts his nemesis.

— Jeff Eldridge