mainstage series

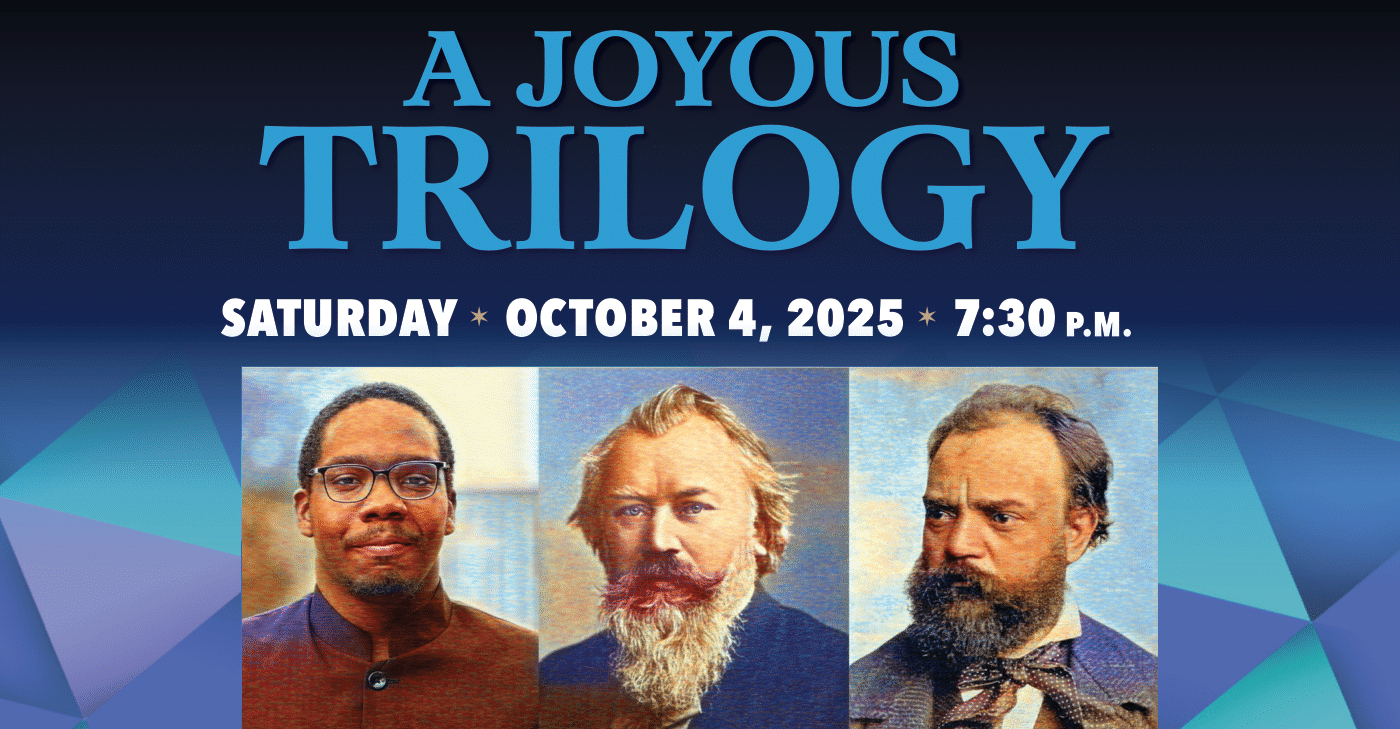

Saturday, October 4, 2025 • 7:30 p.m.

Shorecrest Performing Arts Center (15343 25th Ave NE, Shoreline)

Harmonia Orchestra & Chorus

William White, conductor

Serena Smalley, soprano

Charles Robert Stephens, baritone

Program

Quinn Mason (*1996)

A Joyous Trilogy

Antonín Dvořák (1841–1904)

Te Deum, Op. 103

— intermission —

Johannes Brahms (1833–1897)

Symphony No. 1 in C minor, Op. 68

- full concert program (PDF)

About the Concert

Johannes Brahms struggled for 20 years to compose his first symphony, eventually creating a masterpiece that journeys from tragedy to triumph. Antonín Dvořák (a close friend of Brahms) wrote his Te Deum for his first concert in the New World, a trip that inspired generations of American composers. In early 2020, American composer Quinn Mason conducted the premiere of his A Joyous Trilogy with Harmonia — and from that launching pad has gained an international reputation.

- This performance will last approximately two hours, including one intermission.

- Join music director William White and composer Quinn Mason for a pre-concert talk beginning at 6:30 p.m.

- Streaming tickets are also available for this concert. Due to technical limitations at the performance venue, the program will not be streamed live, but the video will be made available within 48 hours.

Maestro’s Prelude

It is a pleasure — nay, a joy! — to welcome you to Harmonia’s first concert of the 2025–2026 season. The overriding theme this year is “Testaments” and tonight we have a program in which three composers are testifying to their irrepressible and unconquerable joy.

We begin with the eponymous A Joyous Trilogy, a piece that — if I may be so bold as to speak on behalf of the organization — Harmonia is tremendously proud of having brought into existence. When we commissioned the work six years ago, Quinn Mason was little known outside of his native Texas, but since then his music has taken the world by storm, in large part due to this piece. Every month or so, one of my baton-waving colleagues will text me a photo of the first page of the score with “To Will White” printed at the top. Ironically, I (the work’s very dedicatee!) have never actually conducted it, since it was Quinn himself who led the premiere with Harmonia back in February 2020 (making his orchestral conducting debut). Tonight, I look forward to rectifying this situation.

One can only imagine the joy that Antonín Dvořák must have felt when he embarked upon a voyage to New York in 1892, having lived his entire life within the confines of the Austro-Hungarian empire. His excitement comes through loud and clear in his setting of the Te Deum, the last piece he completed before setting sail, specifically intended as his first big premiere in New York. Dvořák’s music makes a natural pairing with a piece by an American composer, given that his presence in the U.S. did so much to inspire generations of composers in our country, but more than that, Dvořák provides the link between the Americans and the great European symphonic tradition, represented tonight by the magisterial first symphony of Johannes Brahms.

Brahms took 21 years to compose this symphony, tinkering with it obsessively until he felt he had achieved a monument that could live up to the standard set by Beethoven. It’s possible that Brahms would have dithered for another decade were it not for his encounter with Dvořák, who — in half that time — had produced five symphonies of his own. Brahms marveled at the vitality of his Bohemian colleague’s music, but it was mainly ’s “don’t let the perfect be the enemy of the good” attitude that was such a healthy influence on his compositional habits. Yet it’s hard to find a better word for this symphony than “perfect,” and no matter how many times I engage with this work, I am always eager to take the ride from turmoil to joyous triumph that Brahms so masterfully created for us.

This program is a real dazzler, but I can assure you that every concert we’ve got in store for you this season is going to be an event. I’m desperate that you not wallow in FOMO, so I would urge you to purchase a season subscription if you haven’t done so already. You deserve it.

— William White

About the Soloists

Soprano Serena Smalley is known for her radiant coloratura, dynamic acting and “magnetic” stage presence (Entertainment News Northwest). Hailed for her vocal agility and expressive nuance, she is increasingly in demand throughout the Pacific Northwest and beyond, where companies and audiences alike turn to her for roles that require both vocal brilliance and dramatic depth. Recent engagements include featured roles such as Musetta (La Bohème), Glauce (Medea), Marie (La Fille du Régiment), Lisa (La Sonnambula) and Nanetta (Falstaff), Rosina (Il Barbiere di Siviglia), and Olympia — the iconic doll — in Les Contes d’Hoffmann. Frequently engaged by Seattle Opera, Ms. Smalley has appeared in both mainstage and touring productions, including The Three Feathers, Die Zauberflöte, La Traviata, Cinderella in Spain and the role of Amore in O+E. She made her Seattle Symphony debut as Queen of the Night in Die Zauberflöte and returned for the sold-out “Joe Hisaishi Returns” concert featuring the Princess Mononoke Suite. A graduate of Indiana University’s Jacobs School of Music, Ms. Smalley studied under legendary soprano Carol Vaness and trained with the OperaWorks Advanced Artist Program in Los Angeles.

learn more: serenatastudios.com

Baritone Charles Robert Stephens has enjoyed a career spanning a wide variety of roles and styles in opera and concert music. In his 20 years in New York City, he sang leading roles with the New York City Opera and was declared by The New York Times to be “a baritone of smooth distinction.” He also appeared frequently in Carnegie Hall with the Opera Orchestra of New York in a variety of roles, and was active in regional opera throughout the U.S. On the international stage, he sang opera roles in Montevideo, Taiwan, Santo Domingo and Mexico City. Now based in Seattle, Mr. Stephens has sung with the Seattle Symphony, Northwest Sinfonietta, Spokane Opera, Portland Chamber Orchestra and many other ensembles and opera companies throughout the Pacific Northwest. Recent performances include Vaughan Williams’ Sea Symphony and Handel’s Messiah (Spokane Symphony), Judge Turpin in Sweeney Todd (Helena Symphony), Bach’s Mass in B minor (St. Paul Music Guild), Mozart’s Requiem (Bellingham Symphony), Mozart’s Mass in C minor (Seattle Pro Musica), Haydn’s The Seasons (Harmonia), Verdi’s Requiem (Symphony Tacoma), and a Paris debut in Bach’s St. John Passion (Les Fetes Galantes).

learn more: charlesrobertstephens.com

Program Notes

Quinn Mason

A Joyous Trilogy

Mason was born March 23, 1996, in Shreveport, Louisiana, and currently resides in Dallas, Texas. He composed this work as the result of a commission from Harmonia for its 50th anniversary season and conducted the world premiere at the Shorecrest Performing Arts Center on February 15, 2020. The score calls for pairs of woodwinds, 4 horns, 3 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, percussion, harp and strings.

Quinn Mason has been described as “a brilliant composer … in his 20’s who seems to make waves wherever he goes” (Theater Jones) and “one of the most sought after young composers in the country” (I). His orchestral music has received performances by renowned orchestras across the United States, including those of San Francisco, Minnesota, Seattle, Dallas, Detroit, Utah, Rochester, Fort Worth, Vermont, Rhode Island, Amarillo, Memphis, Toledo and Wichita, plus the National Youth Orchestra of the United States, New World Symphony, University of Michigan Symphony and National Orchestral Institute Philharmonic, as well as numerous youth orchestras, Scotland’s Nevis Ensemble, Italy’s Orchestra Sinfonica Nazionale della RAI and England’s Sheffield Philharmonic. His works for wind ensemble have been performed throughout the United States and Canada.

Mason studied composition at Southern Methodist University’s Meadows School of the Arts and with Winston Stone at University of Texas at Dallas, and has worked closely with renowned composers David Maslanka, Jake Heggie, Libby Larsen, David Dzubay and Robert X. Rodriguez. The recipient of numerous awards (from the American Composers Forum, Voices of Change, Texas A&M University, ASCAP and the Dallas Foundation, among many others), he was honored by The Dallas Morning News as a 2020 finalist for “Texan of the Year.” He considers it his personal mission to create music “based in traditional classical music, but reflecting the times in which we live.”

A Joyous Trilogy was commissioned by Harmonia music director William White, to whom Quinn Mason dedicated the work, calling him “a friend and mentor for many years now, and one of the most joyous people I know!” A “set of three short symphonic sketches for large orchestra” played without pause, A Joyous Trilogy had its genesis in “a piece I wrote in 2017, titled Passages of Joy,” premiered on January 21, 2019, by the South Bend Symphony Orchestra under the direction of Alastair Willis: that work formed the basis of the first movement of A Joyous Trilogy.

Mason “wanted to create a composition that was the very embodiment of happiness and cheerfulness, an accessible work that would put any listener in a good mood. The first movement, ‘Running,’ is so called because of its always-moving and seemingly never-waning energy. The second, ‘Reflection,’ is a gentle meditation featuring a solo trombone. “The third, ‘Renewal,’ picks the energy back up and keeps it going to the very end.”

Antonín Dvořák

Te Deum, Op. 103

Dvořák was born September 8, 1841, in the Bohemian town of Nelahozeves (near Prague, now in the Czech Republic), and died on May 1, 1904, in Prague. He composed this work between June 25 and July 28, 1892, conducting the premiere at Carnegie Hall on October 21 of that year. In addition to vocal soloists and SATB chorus, the work calls for pairs of woodwinds (with one oboe doubling English horn), 4 horns, 2 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, triangle, cymbals, bass drum and strings.

This work (along with Dvořák’s most famous composition, the “New World” Symphony) may never have come to be were it not for New York philanthropist Jeannette Meyer Thurber (1850–1946). In 1885 she founded the National Conservatory of Music in America, modeled after the Paris Conservatoire (where she had studied as a teen). Jacques Bouhy, a renowned Belgian baritone who had created the role of Escamillo in Carmen, served as the school’s first director. The Conservatory had a remarkably progressive admissions policy, encouraging women, minorities and the physically disabled to enroll, and arranged for students to attend regardless of their ability to pay tuition. Deciding to hire a top-rank composer to succeed Bouhy, Thurber set her sights on Antonín Dvořák.

Trained as an organist, Dvořák played viola in Prague’s Bohemian Provisional Theater Orchestra during the 1860s, supplementing his income by giving piano lessons. Although his Op. 1 dates from 1861, his music apparently received no public performances until a decade later, when he quit the orchestra to devote more time to composing. While his music began to achieve some measure of success in Prague, he remained in need of two things: money and wider recognition of his talents.

In 1874, Dvořák applied for the Austrian State Stipendium, a composition prize awarded by a jury consisting of composer Johannes Brahms, music critic Eduard Hanslick and Johann Herbeck, director of the Imperial Opera. Brahms in particular was overwhelmingly impressed by the 15 works Dvořák submitted, which included a song cycle, various overtures and two symphonies. Dvořák received the 1874 stipend, and further awards in 1876 and 1877, when Hanslick wrote to him that “it would be advantageous for your things to become known beyond your narrow Czech fatherland, which in any case does not do much for you.”

Seeking to help in this regard, Brahms passed along a selection of Dvořák’s music to his own publisher, Fritz Simrock, who issued Dvořák’s Op. 20 Moravian Duets, then commissioned some four-hand–piano pieces modeled after Brahms’ successful Hungarian Dances. These Op. 46 Slavonic Dances proved so popular that they launched Dvořák’s worldwide fame.

In the spring of 1891, shortly after Dvořák became a professor of composition at the Prague Conservatory, Thurber offered the composer a job as director of her school in New York — at 25 times his current salary. Negotiations ensued over the next few months until Dvořák, initially reluctant, accepted. His contract required him to give six concerts annually, and one of these was planned for shortly after his arrival, to be held on October 12, 1892, at the Metropolitan Opera House in celebration of the 400th anniversary of Columbus landing in the Western Hemisphere.

Thurber asked Dvoˇrák to compose a choral work for the event, setting an 1819 poem by Rodman Drake that extolled the virtues of the U.S. flag. The text did not arrive in a timely manner, however, so the composer went with Thurber’s suggested backup plan “that Dr. Dvořák choose some Latin Hymn such as Te Deum laudamus or Jubilate Deo or any other which would be suitable for the occasion.” Dvořák opted for a Te Deum. Meanwhile, a fire at the Metropolitan Opera forced the cancellation of their 1892–1893 season and necessitated moving the Dvořák welcoming concert to October 21 at the newly opened Carnegie Hall:

A devout Catholic, Dvořák had previously composed two lengthy settings of religious texts — a Stabat Mater (written in 1876 and 1877 as a reaction to the death, in quick succession, of three of his children) and a Requiem (on a commission from a music festival in Birmingham, England, where he conducted the premiere in 1891) — along with a brilliant setting of Psalm 149 and a Mass in D major (composed in 1887, but orchestrated in 1892 immediately before he began writing the Te Deum).

The Te Deum is a Christian hymn of praise probably dating from the fourth century. Lully, Handel, Haydn, Mozart, Berlioz, Verdi and Bruckner all created settings of the text, typically for ceremonial occasions of public rejoicing. broke the text into four sections, creating a miniature symphony that shares an opening key (G major) and a general pastoral mood with his Symphony No. 8, composed three years prior.

Pounding timpani open the work, with the chorus exulting in praise of the Lord. The music softens for the central “Sanctus” section, led by solo soprano. A brief reprise of the boisterous opening material leads without pause to the slow movement, which alternates dramatic brass fanfares with the baritone soloist singing “Tu Rex gloriae, Christe.” The mood eventually relaxes, with the chorus (first upper voices, then lower) answering the soloist (“Te ergo quaesumus”).

The third movement takes the form of a symphonic scherzo, leading directly to the finale, initially dominated by the solo soprano. The baritone soloist joins her for the “Benedicamus” before material from the first movement returns for a brilliant “Alleluja!”

Johannes Brahms

Symphony No. 1 in C minor, Op. 68

Brahms was born in Hamburg on May 7, 1833, and died in Vienna on April 3, 1897. He began sketching materials for his first symphony as early as 1855, but did not start assembling these ideas in earnest until about 1874. He completed the work during the summer of 1876, while staying at the resort of Sassnitz in the North German Baltic islands; it debuted on November 4, 1876, at Karlsruhe, under the direction of Otto Dessoff. Brahms continued to revise the symphony, particularly the two central movements, over the course of the next year. The score calls for pairs of woodwinds (plus contrabassoon), 4 horns, 2 trumpets, 3 trombones, timpani and strings.

The middle son of a working-class musician and a seamstress, Johannes Brahms began his musical studies on violin and cello. At age seven, he demanded to learn the piano, despite the Brahms family not having a keyboard (or the means to acquire one). Hannes displayed such a remarkable talent that three years later his first teacher declared that he had taught Brahms everything he could and handed him over to Eduard Marxsen, a respected piano pedagogue and published composer described by Brahms biographer Jan Swafford as “Hamburg’s most prominent musician in those days.” Hannes begged for composition lessons alongside his piano studies. Marxsen eventually gave in.

Marxsen schooled Brahms in the music and techniques of the masters, with Hannes playing and studying Bach, Mozart and Beethoven rather than such “modern” com- posers as Frédéric Chopin or Robert Schumann. When Luise Japtha, an older Marxsen pupil, showed Brahms a Schumann aria, he pointed out its technical faults. Never-

theless, in March 1850 when the renowned pianist Clara Wieck Schumann arrived in Hamburg to play her husband’s concerto with him conducting the Hamburg Philharmonic, Brahms sent a packet of his compositions to the Schumanns’ hotel seeking comment. It was returned unopened. This sank Hannes’ opinion of Robert Schumann even further.

In April 1853, Brahms set out on a concert tour with Eduard Hoffmann, a Hungarian political exile who had renamed himself Ede Reményi. Toward the end of May, they arrived in Hanover, where Reményi looked up an old Hungarian acquaintance, the virtuoso violinist, conductor and composer Josef Joachim. Only two years older than Brahms, Joachim had begun touring as a child prodigy and had almost single-handedly forged a place for the Beethoven concerto in the standard repertoire. “Never in the course of my artistic life,” the famed violinist would remember half a century later, “have I been more completely overwhelmed” as when Brahms sat down to play for him. The young man’s compositions simply blew him away.

On August 26, Brahms set out from Mainz on a hiking tour of the Rhine. Joachim implored him to call on the Schumanns when he reached Düsseldorf. Brahms was not so sure that he would, but in the end he listened to Joachim. Robert reacted enthusiastically to Brahms’ compositions, returning to music criticism to author an article, “Neue Bahnen” (“New Paths”) in Neue Zeitschrift für Musik (a journal he had founded in 1834) that praised the young composer as someone “fated to give expression to the times in the highest and most ideal manner.” (The implication being that Brahms provided an alternative to the “music of the future” championed by Franz Liszt and Richard Wagner.)

Schumann’s praise vaulted Brahms to fame at an early age but brought with it a heavy burden. For a time (during Robert’s illness that led to his death and 1856, and Johannes’ lovesickness for Clara) Brahms became unable to compose. From their first meeting, the Schumanns urged him to write for orchestra, but Marxsen had neglected to teach him orchestration and the shadow of Beethoven loomed. (“You have no idea what it’s like to hear the footsteps of a giant like that behind you.”) For the longest time he avoided two genres inextricably linked to Beethoven: symphony and string quartet. And he would never write an opera (not for lack of trying to find a suitable libretto), although that had more to do with Wagner than Beethoven.

By his own accounting, Brahms composed and burned at least 20 quartets before he published an entry in that genre. Symphonies would wait even longer. He began sketching a symphony in D minor not long after meeting the Schumanns, but that music found its way into his first piano concerto and his German Requiem. Then came two multi-movement orchestral works he dubbed “serenades,” looking back to Mozart and Haydn rather than Beethoven.

Beethoven’s Ninth would eventually inform Brahms’ conception of his own first symphony, but so would Beethoven’s Fifth — — — especially in the choice of key, C minor. Sketches for the first movement of a C-minor symphony date from as early as 1855, but it took two decades before he could solve the problem of how to handle a finale and find the appropriate structures for the middle movements.

Brahms originally began the opening movement of his first symphony at the point where the orchestra now launches into the Allegro tempo — in fact, the composer sent a piano score of the movement to Clara Schumann in this form — but he later added a slow introduction that establishes several of the movement’s important themes; this opening material returns — not quite as slowly — in the first movement’s coda. For the most part, Brahms follows traditional sonata-allegro form, but offers up some surprises as well: ordinarily a C-minor first theme would give way to an E♭-major second theme — it does, but then a violent E♭-minor episode follows to close out the exposition.

Employing a technique he learned from Beethoven, Brahms casts the slow(ish) second movement in E major, harmonically far removed from the C minor of the opening. These keys, at an interval of a major third, establish a pattern that persists throughout the rest of the work, moving up another major third to A♭ major for the third movement, and then to C minor/major for the finale.

In his symphonies, Brahms diverged from Beethoven’s model in one important way: in place of a quicksilver scherzo, Brahms opts for a more relaxed, intermezzo-style third movement, often in 2/4 time (as it is here) instead of the traditional (and much faster) 3/4. Solo clarinet sings the opening melody: a five-bar phrase that is then repeated upside-down. “The middle section” of the A–B–A movement, writes Swafford, is “dominated by grand flowing woodwind and brass lines” with “a touch of fatalism in its insisted repeated notes.”

The introduction to the final movement opens slowly and in C minor: following a descending figure from low strings and contrabassoon, the first violins hint at a melody that will soon take on great importance; a pizzicato episode follows and the tempo accelerates, then suddenly relapses as these two ideas repeat. A syncopated rhythm, swirling from the depths of the orchestra, creates great urgency — then the clouds part and a magnificent horn solo signals the arrival of C major. (Brahms had sketched this horn melody on a birthday card to Clara Schumann several years before, attaching the message, “High on the mountain, deep on the valley, I send you many thousands of greetings.”) Next comes a chorale stated by trombones and bassoons, after which the horn call returns, but now developed much more elaborately, subsiding to a simple dominant chord — how will it resolve?

Brahms here introduces his “big tune,” the melody suggested by violins at the opening of the movement, now stated in full. (When someone pointed out to the composer the resemblance of this tune to the “Ode to Joy” melody of Beethoven’s Ninth, the composer reportedly responded, “Any ass can hear that.”) Brahms develops the violin theme, alternating it with other material from the slow introduction, building in fervor. Eventually, the bottom seems to drop out and the tempo slackens for a passionate reprisal of the Alpine horn call. A recapitulation section follows, yet the “big tune” is absent. This leads to a faster coda, which seems intent on driving the movement to its conclusion, but Brahms interrupts with a fortissimo restatement of the trombone chorale from the introduction. A new syncopated triplet rhythm returns the coda to its faster pace and leads to the symphony’s triumphant finish.

— Jeff Eldridge